Revisions on Genesis 1:1-13

Working with the garage door up, solving problems, finding new problems, fixing mistakes.

I’ve always worked best with the garage door up, and that means posting early attempts at translation, followed by revisions. I started translating Genesis five years ago, then had to put the project aside with the birth of my daughters, and it’s been interesting to revisit and revise that old work. Sometimes dismaying.

There are a number of problems I fixed in this revision. The first is the translation of בָּרָ֣א in the first verse. My initial choice, made, was untenable because it doesn’t have the consonance of the Hebrew (beresheit bara) and complicates translating עשׂה in later verses. I’ve settled on built. This has the consonance. Yes, it stretches the meaning of בָּרָ֣א a bit. It stretches the meaning, but it doesn’t break it. Again and again God, the prophets, and the psalmist refer to the creation as building:

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?—Job 38:4 (cf. Psalm 102:25, Isaiah 51:13, etc)

Who has measured the waters in the hollow of his hand and marked off the heavens with a span, enclosed the dust of the earth in a measure and weighed the mountains in scales and the hills in a balance?—Isaiah 40:12

The next problem I worked on is what to call God. Initially, I translated אֱלֹהִים as God in the first verse, and then in all the subsequent repetitions I used He. While this read well, I’ve decided it is too much of an innovation, and it papered over the interesting verses in the first chapter in which there is only an implied third person masculine pronoun (Hebrew verbs have number and gender and can thus imply an unwritten subject) and thus He does make sense. This problem of naming God will become more acute when the tetragrammaton appears. (In our conversation the other day, Everett Fox discussed his approach to the tetragrammaton problem and the approach of Buber & Rosenzweig.)

I’ve also made line breaks more consistent and found other ways to be faithful to the goal of brevity. And fixed a few glaring mistakes and omissions.

The revision:

Beginning

God built

Heavens and Earth

Earth

wild and wooly

Darkness

on deep

God’s breath

over Water

God said, “Light”

So light was

God saw Light

was fine

God cut

Light

from Dark

God called Light

day

Dark

He called night

An evening, a morning

one day

God said, “Sky

among Waters

cutting between

water and water”

God made Sky

God cut between

Water under Sky

and Water above

God called Sky

heavens

An evening, a morning

second day

God said, “Water

below Heavens

together in one place”

Land appeared

God called Land

earth

The water place

He called

sea

God saw

that was fine

God said, “Earth, sprout

plants

each with

its own seeds

trees

each with

its own fruit

with its seed

on Earth”

Earth birthed

plants

each with

its own seeds

trees

each with

its own fruit

with its seed

on Earth

God saw

that was fine

An evening, a morning

third dayA final thought: when St. Paul encountered Christ on the road to Damascus, he did not understand himself to be converting to a new religion.1 One of my goals has been to bring together the wisdom of the old rabbinic commentaries with those of the Church Fathers. The term “Judeo-Christian” is an overused cliché,2 but there are cases in which it is meaningful, such as the 13th C. Franciscan teacher Nicholas of Lyra (or, in the other direction, Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik). Or, dare I say, St. Jerome.

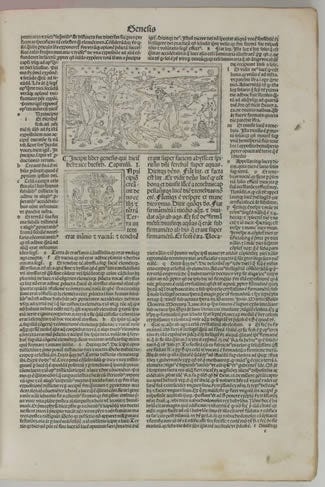

I hope that this project can be meaningfully “Judeo-Christian” in the example of Nicholas, who even printed his commentaries in the Jewish style:

Thank you to all who’ve subscribed. If you haven’t yet, please:

And does it make sense to talk about Judaism or Orthodox Christianity as “religions”? Or is that word, as it’s used today, a Protestant category? See Leora Batnitzky’s How Judaism Became a Religion.

See Arthur A. Cohen’s The Myth of the Judeo-Christian Tradition.