My last post here was in August 2023. I apologize for the long delay. Over that period I started a small high school program, so I have been teaching Homeric Greek (and literature, mathematics, etc) to teenagers. And neglecting my Hebrew! The Genesis translation is something I vow to finish someday, but in the meantime I want to share my rough translation of the first five lines of the Iliad.

A professor once told me that if I really wanted to learn Greek, I needed to teach it, and that has turned out to be true. I’ve learn a lot teaching Greek. When I sat down with the Homer’s proem, it was nice that I could simply read it without the aid of grammar notes or lexicon.

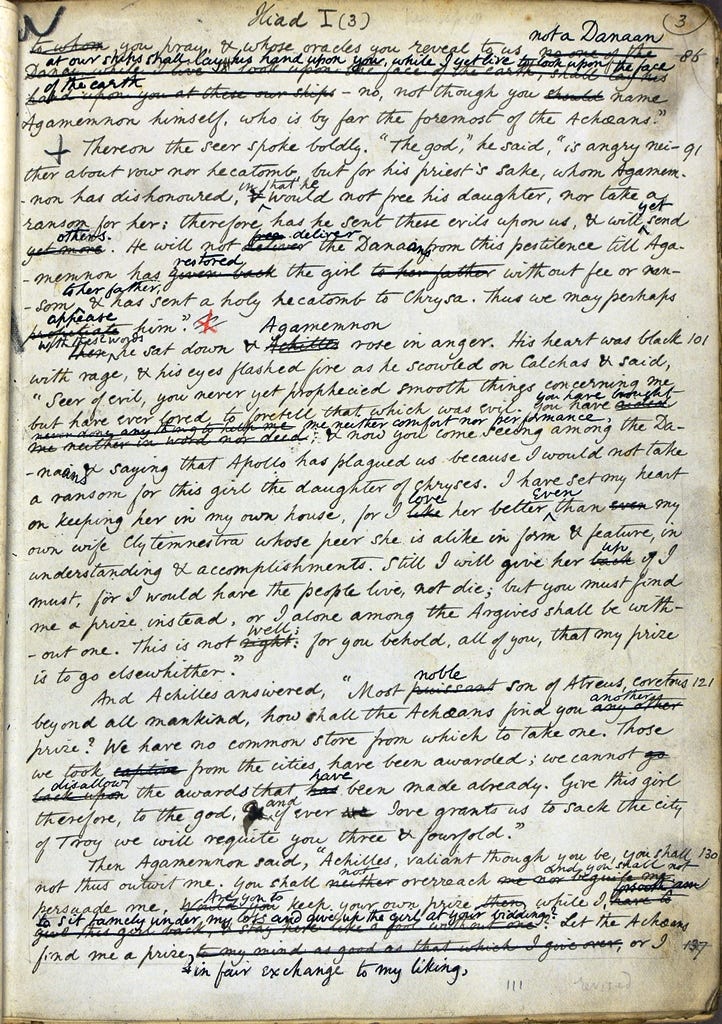

This week my students took a stab at translating Homer, so I joined them. We also read Lydia Davis’ wonderful essay “21 Pleasures of Translating”.

Here are the first five lines in Greek:

μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί᾽ Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε᾽ ἔθηκε, πολλὰς δ᾽ ἰφθίμους ψυχὰς Ἄϊδι προΐαψεν ἡρώων, αὐτοὺς δὲ ἑλώρια τεῦχε κύνεσσιν οἰωνοῖσί τε δαῖτα, Διὸς δ᾽ ἐτελείετο βουλή

The first things that jump out at me in these lines are the enjambment in the first and second clauses (μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος / οὐλομένην and πολλὰς δ᾽ ἰφθίμους ψυχὰς Ἄϊδι προΐαψεν / ἡρώων) and the parallel phrases ἑλώρια κύνεσσιν and οἰωνοῖσί δαῖτα. (Some manuscripts read “πᾶσι” instead of “δαῖτα”, but I take “δαῖτα” there. Thomas Seymour, 1891, calls δαῖτα “the food of brutes”.)

My translation:

Accursed Wrath of Peleus' Achilles,

sing of it, goddess,

wrath that put a hurt on countless Achaeans,

sent many mighty souls of heroes

to Hades,

made them detritus for dogs,

banquets for birds,

Zeus's plan being accomplished... So many problems to solve!

Lydia Davis’ second pleasure of translating is that you are “always solving a problem”:

In translating, then, you are at the same time always solving a problem. It may be a word problem, an ingenious, complicated word problem that requires not only a good deal of craft but some art or artfulness in its solution. And yet, though the problem is embedded in a text of great inherent interest, even importance, it always retains some of the same appeal as those problems posed by much simpler or more intellectually limited word puzzles in the daily or Sunday paper or in a slim book picked up at a train station— a crossword, a Jumble, a code.

One problem is how to split up Homer’s lines. Do you translate line by line (as Herbert Jordan does in his brilliant translations)? Or clause by clause? Or idea by idea? Or something else?

Here’s Jordan:

Sing, goddess, of Peleus' son Achilles' anger, ruinous, that caused the Greeks untold ordeals, consigned to Hades countless valiant souls, heroes, and left their bodies prey for dogs or feast for vultures. Zeus's will was done...

Somehow he finds an elegant way to follow Homer’s enjambment (“anger,/ ruinous” and “souls,/ heroes”) that still reads well in blank verse. This is a good example of why Jordan’s translations are the best. He taught himself Greek as a grief project after the death of his son, and when he translated the light was shining on him.

But not on me. So I abandon Homer’s lines and meter for a free verse approach. I have to repeat “wrath” in my third line to make the syntax work. I use consonance with “detritus for dogs” / “banquet for birds”. Webster’s 1913 gives detritus as “Any fragments separated from the body to which they belonged; any product of disintegration.” LSJ gives banquet as one definition of δαῖτα; my choice for consonance isn’t a stretch. “Put a hurt on” might seem like an eccentric translation of ἄλγε᾽ ἔθηκε, but it’s painfully literal. ἔθηκε is the aorist form form of τίθημι: to put or place.

It feels good to translate again! I realize this is a Substack devoted to Bible translation, but I hope you will forgive my return here to translate the greatest pagan poet.